(back to the Documentation)

International climate policy agreements

1. The beginning of an international climate policy

2. The Montreal Protocol

3. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

4. The Kyoto Protocol

5. The EU Emission Trading Scheme

1. The beginning of an international climate policy

Climate has always been a crucial interest for human beings seeing that it has a huge impact on several essential activities, like agriculture for example. It is thus not surprising that as early as 1873 the International Meteorological Organization was founded and became in 1951 the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the specialized UN agency in charge of weather, climate, operational hydrology and related geophysical sciences.

Several years after the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, Environment & Development) in 1972, an international alert signal about the risk of climate change due to anthropogenic activities was "cried out" during the first World Climate Conference (1979) under the aegis of the WMO. The World Climate Programme (WCP), overseen by the WMO, the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO, was established at this time.

The second important signal took place in 1985 at the International Conference, jointly organized by UNEP, WMO and ICSU (International Council for Sciences), on the "Assessment of the role of CO2 and of other greenhouse gases in climate variations and associated impacts" with several recommendations encouraging governments to take these assessments into account in their policies, to raise public awareness, to support scientific research on climate change and monitoring of emissions, to find alternative development pathways to mitigate GHG emissions or solutions to tackle climate impacts.(1)

WMO and UNEP joined efforts again in 1988 with the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) aiming at assessing "on a comprehensive, objective, open and transparent basis the best available scientific, technical and socio-economic information on climate change from around the world. (…) IPCC reports seek to ensure a balanced reporting of existing viewpoints and to be policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive." (2). The IPCC publishes regularly assessment reports summarising scientific progress in the knowledge about climate change (atmospheric chemistry and dynamics, progress in mitigation/adaptation technologies, impacts, etc.), and regularly special reports on precise subjects (e.g.: special report on "Aviation and the global atmosphere", 1999), technical and methodology reports.(3)

The same year, the UN adopted the resolution 43/53 on the "Protection of global climate for present and future generations of mankind" (4). In this resolution climate is considered as part of the common heritage of mankind that can be severely altered by human activities. Therefore, member states, NGOs and the scientific community are invited to work on the development of a common programme to study and stabilise the climate change.

2. The Montreal Protocol

Originally the Montreal Protocol had no direct link with the climate policy since it was designed in 1987 by UNEP to tackle the problem of substances that deplete the ozone layer, mainly halogenated hydrocarbons containing either chlorine (CFCs or chlorofluorocarbons) or bromine (halons). Those ozone-depleting substances are also powerful greenhouse gases.

The depletion of the stratospheric ozone has as environmental consequence that more ultraviolet-B radiation reaches the surface of the planet, inducing higher risk of skin cancer, damage to crops and to marine phytoplankton.

Unfortunately, it has been now proved that several alternatives substances, HCFCs (hydrochlorofluorocarbons) and HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons), used to replace the progressively phased-out ozone-depleting substances, still have a great potential impact on global warming (cf. great Global Warming Potential). The protocol calls for a complete phase-out of HCFCs by 2030 in developed countries and by 2040 in developing countries, but does not place any restriction on HFCs up to now.

However, the contribution of ozone-depleting substances to climate change most likely would have been greater without the Montreal Protocol regulations.

In the light of such a development, the Montreal Protocol should be considered as one of the instruments for an international climate policy aiming at mitigating greenhouse gases, even if its main objective still consists of protecting the stratospheric ozone layer. Additional effort to manage the emissions of substitute fluorocarbon gases and/or to implement alternative gases with lower climate impact are supporting and/or complementing targets set in other international agreements specifically dedicated to global warming (see further: UNFCCC, Kyoto Protocol).

Transport was not targeted speaking as itself by the protocol but many substances covered are/were in use within the sector, such as refrigerants in refrigerated vehicles for fresh goods, gases used in air conditioning systems, etc. Major stake in the future to reduce these substances would be to replace current cooling fluids by other substances or mixes of substances having a lower global warming potential.

3. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (4)

In 1992, during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) - also called the "Rio Earth Summit" -, it was decided to sign an international treaty, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in order to tackle the phenomenon of global warming through the reduction of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

3.1. Introduction to the UNFCCC

3.1.1. Fundamental principles

The treaty recognises the nature of a "common resource to be protected" to climate and the human responsibility related to the accumulation of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere at a concentration level far higher than former historical concentrations. The convention aims at achieving "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a low enough level to prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner." (UNFCCC, art.2).

The conditions for its entry into force were fulfilled on 21 March 1994. The convention has been adopted up to now by 192 countries (by ratification, acceptance, approval or accession) (5).

This convention is a legally non-binding instrument and sets no mandatory limits on GHG emissions, but one of the major objectives of this convention are to consider different options to reduce global warming and to cope with the potential temperature increases.

The basis principle of the convention depends on the recognition of a "common but differentiated responsibility" (6) and on the "respective capabilities" (7) of the signatory states (Parties to the convention). The responsibility factor of a country is measured by dividing its total CO2-equivalent emissions by its number of inhabitants. The capability factor is measured by dividing the GDP of the country by its number of inhabitants.

It is also interesting to note that the convention points out the use of the precautionary principle in case of "serious or irreversible damage" and "lack of full scientific certainty".

3.1.2. Commitments

The two main commitments agreed by Parties by adopting the UNFCCC concern the annual national inventory of anthropogenic GHG emissions (sources and sinks), other than those included in the Montreal Protocol, and the national communication on progress of the implementation, realised in accordance with art.12.

Parties commit also to set up national and/or regional programmes with measures aiming at mitigating GHGs and helping to adapt to climate change, to promote and to cooperate to the transfer of technologies and good practises to tackle global warming, to manage in a sustainable way and to conserve sinks and reservoirs of GHGs, to cooperate on adaptation and to set up integrated management plans for coastal zones/water resources/agriculture/the rehabilitation of areas affected by drought and desertification or by floods, to take considerations on the climate change into account in other policies or actions, to cooperate at the scientific and educational levels.

3.1.3. Party grouping

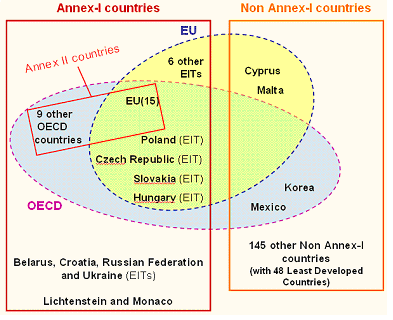

The differentiation principle is to be found again in the way the 189 Parties are categorised.

Annex I countries

Annex I is a list containing 40 developed countries (among which 28 of the 30 OECD member states(8)) plus the EU, including:

- a sub-list of 24 countries plus the EU (Annex II) required to provide developing countries with financial resources and technology transfer to help them to mitigate GHG emissions and to adapt to climate change, and

- a sub-list of 14 countries with Economy in Transition (EIT).

Giving that Annex-I countries are considered as major contributors to the GHG accumulation in the atmosphere, these countries agreed to be subject to an individual commitment to stabilize their GHG emissions at the level of 1990 emissions. No penalty was planned in case they do not respect this objective.

Non Annex-I countries

This list gathers the other Parties to the convention and contains a sub-list of 48 Least Developed Countries (LDC) which are given special consideration under the convention considering their limited capacity to respond to climate change and to adapt.

Current country classifications within the UNFCCC (Annex-I, non Annex-I, Annex II)

|

Other party groupings

During the negotiations, other kinds of Party grouping are regularly observed according to the characteristics or interests of the countries:

- the five distinct regional groups: African states, Asian states, Eastern Europeans states, Latin American and the Caribbean States, Western European and Other States (Australia, Canada, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States of America);

- the Group of 77 (since 1964) represents 130 developing countries and contains different sub-groups with diverging interest on climate change issues: African UN regional Group, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS, a coalition of 43 countries that are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise), the group of Least Developed Countries (an association of 48 countries);

- the European Union (27 members);

- the Umbrella Group is a large association of non-EU developed countries (Australia, Canada, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, the Russian Federation, Ukraine and the US);

- the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) is more recent and consists of Mexico, the Republic of Korea and Switzerland;

- the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries);

- the Central Group (Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania);

- the CACAM (group of countries of Central Asia, Caucasus, Albania and Moldova);

- the League of Arab States;

- the Agence intergouvernementale de la francophonie;

- etc.

3.2. Convention bodies

In order to implement and modify convention commitments, three specialized bodies have been set up with specific objectives and competences, as well as different expert groups:

- the Conference of the Parties;

- the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice;

- the Subsidiary Body for Implementation

- the constituted bodies (expert groups).

3.2.1. The Conference of the Parties (CoP)

The CoP is the association of all Parties to the Convention that meets every year and is the highest decision-making authority. It is responsible for controlling the implementation of the Convention and commitments, for reviewing national communications and emission inventories, for taking into account most recent scientific knowledge and experience gained in implementing climate change policies.

The Bureau of the Conference of the Parties consists of one president, 7 vice-presidents, both chairs of the Subsidiary Bodies and the rapporteur.

3.2.2. Subsidiary bodies

Two permanent subsidiary bodies give advice to the CoP, meet in parallel at least twice a year, and tackle together subjects common to both areas of expertise.

Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice (SBSTA)

It gives advice to the CoP on subjects related to scientific, technological and methodological matters.

Its two main missions consist of elaborating guidelines for national communication and emission inventories, and promoting the development and transfer of environmentally-friendly technologies.

It plays also the role as interface between scientific expert sources and the policy-oriented needs of the CoP.

Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI)

It gives advice to the CoP on all matters concerning the implementation of the Convention, and also on budgetary and administrative matters.

Its key tasks are to examine the information given in the national communications and emission inventories of the different Parties in order to estimate the effectiveness of the Convention, to review the financial assistance given to Non-Annex I Parties in order to help them to respect their commitments, and to give advice to the CoP on guidance to the financial mechanism.

Constituted bodies

Three expert groups have been set up under the Convention:

- the Consultative Group of Experts on National Communications from Non-Annex I Parties (CGE ; CoP5 1999): 14 experts;

- the Expert Group on Technology Transfer (EGTT ; Marrakech Accords of CoP7, 2001): 20 experts;

- the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG ; Marrakech Accords of CoP7, 2001): 12 experts.

3.3. The UNFCCC and the transport sector

As already mentioned, international air and maritime transports were not included in the UNFCCC.

This is mainly due to the fact that the emission allocation principle used in the Convention is based on the territory where emissions occur, which suit to emission from stationary installations or terrestrial transport modes such as road and rail transport but is completely unsatisfactory for emissions related to international transport modes like aviation and maritime transport (cf. most emissions occur above international territories like seas, oceans, etc. and are difficult to allocate to one or another country).

ICAO and IMO were asked to co-operate with the SBSTA to find a compromise concerning the allocation of international GHG emissions. However, this formal demand has still not significantly progressed up to now, despite the different allocation options suggested by the SBSTA.

4. The Kyoto Protocol

The ratification of the UNFCCC in 1994 has rapidly been considered insufficient in order to limit climate change due to human emissions of GHGs and their accumulation in the atmosphere.

4.1. Introduction

It was thus decided in 1997 to set up a complementary accord (in fact a constitutional amendment to the UNFCCC) in the same framework - the Kyoto Protocol - to fix quantitative objectives for the reduction of 6 priority-holder GHGs (see Annex A (9) of the protocol):

- CO2 (carbon dioxide),

- CH4 (methane),

- N2O (nitrous oxide),

- HCFCs (hydrofluorocarbons),

- PFCs (perfluorocarbons),

- SF6 (sulphur hexafluoride).

GHGs are expressed in a common unit called tonne of CO2-equivalent (t CO2 eq.). The equivalence between a mass of a specific GHG and the corresponding mass of CO2 eq. is determined by the Global Warming Potential (GWP) set by scientists and associated to this specific GHG.

Annex A of the protocol lists also the different sectors covered by the emission reduction target:

- energy (fuel combustion and fugitive emissions from fuels);

- industrial processes;

- solvent and other product use;

- agriculture;

- waste.

4.2. Basic principles

The objective of the protocol is to reduce the 1990 (10) emission level of these GHGs by at least 5.2% globally for Annex-I countries of the UNFCCC, during the first commitment period of 2008-2012.

Annex B of the protocol enumerates the legally-binding individual figured targets for each concerned country. Some Annex-I countries like the USA and Turkey have not ratified the Kyoto Protocol yet.

No quantitative objectives are set for developing countries for two main reasons:

- industrialised countries are considered as responsible for a majority of past and current emissions on the one hand, and

- developing countries fear that a strict emission objective could hinder their economic development on the other hand.

Up to now, 176 countries and the EU have ratified the Kyoto Protocol.

4.3. Allocation principle

4.3.1. Description

The allocation principle aims at attributing covered GHG emissions to the different Parties to the protocol. It was adopted with the objective of limiting evasion potentials and according to data availability.

Seeing that covered emissions are mostly attributable to a well identified country, emissions have been allocated on the basis of the place where there occur. The reduction effort has been negotiated and calculated then for each industrialized country (Annex I to the UNFCCC) according to the differentiate responsibility and capacity principles.

4.3.2. The European "bubble"

Within the UNFCCC-Kyoto Protocol scheme, the EU(15) received a general emission reduction target of -8% in comparison with the 1990 GHG emission level (art.4 of the protocole). This is called the European Bubble.

The burden sharing (Council Decision 2002/358/EC) took place between the 15 Member States on the basis of the triptych aproach, a sector-based allocation principle including the energy sector, the industry and domestically oriented sectors.

Within those sectors, the reduction effort has been distributed according to a benchmark :

- in the energy and industry sectors, benchmarks refer mainly to energy efficiency indicators;

- while in domestically-oriented sectors, the benchmark allocates the emission allowances per capita.

While the ten new Member States negotiated each an emission reduction objective comprised between -8% and -6% in comparison with a year of reference (not necessarily 1990), Cyprus and Malta have no emission reduction target at all.

4.4. Flexible mechanisms

Kyoto targets for Annex B countries are mandatory and quite strict. In order to facilitate their compliance at a lesser cost, the protocol set up four different mechanisms to help concerned Parties :

- to reduce their GHG emissions or increase their GHG adsorption by the mean of an economic incentive (the Emission Trading system, defined in art.17) or

- to compensate for GHG emissions emitted above their Kyoto target by reducing GHG emissions or increasing GHG adsorption, in comparison with a baseline scenario, in other countries (the Clean Development Mechanism, defined in art.12, and the Joint Implementation, defined in art.6).

Even if these flexible mechanisms were already mentioned by the protocol in 1997, the practical aspects were fixed during the seventh CoP in 2001 leading to the "Marrakech Accords". Modalities and procedures adopted were in fact the legal translation of the principles decided in the Buenos Aires Action Plan (1998).

Among these modalities, five basic principles were decided to become an eligible actor for the flexible mechanisms. Candidate country has to:

- be a Party to the Kyoto Protocol;

- have calculated its "Assign Amount" (11) (in order words, be an Annex-I Party having ratified the protocol and having negotiated a Kyoto target);

- have set up a national system for the follow-up of GHG emissions and adsorptions;

- have created a national registry dedicated to the accounting of Kyoto Protocol units (AAUs, ERUs and CERs ) taking into account deliverances, transfers, and cancellations;

- submit annually to the UNFCCC secretariat its GHG emission inventory and other information required.

4.4.1. Emission Trading (ET)

It is a market-based system that in principle allows entities the flexibility to select cost-effective solutions to achieve established environmental goals.

By means of this mechanism, Annex-I countries may sell or buy AAUs / RMUs / CERs / ERUs to or from other countries.

4.4.2. Land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) activities

Following specific activities related to the LULUCF sector will be the only admissible "sink" activities during the first commitment period (2008-2012) of the protocol:

- afforestation , reforestation and deforestation (taking into account eligibility criteria defined by the protocol);

- forest management, cropland management, grazing land management and revegetation (added to the eligible LULUCF activities by the Marrakech Accords).

4.4.3. Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)

With this mechanism, developed countries may invest in GHG emission reduction or removal projects in developing countries. They receive therefore a certain amount of Certified Emission Reduction units (CERs), that they may use to comply with their Kyoto target (offset of emissions above the limit fixed).

In CDM projects, credits are granted only to emission having been reduced or removed in comparison with a baseline scenario estimating the "normal" trend of GHG emissions in the host country.

4.4.4. Joint Implementation (JI)

The JI mechanism works on the same principle as the CDM but this time, the host country is a developed country (mainly Economies In Transition). The credits received by the investing country are called Emission Reduction Units (ERUs).

4.5. Kyoto Protocol bodies

Kyoto Protocol bodies consist of UNFCCC bodies and some constituted bodies dedicated to specific tasks of the Kyoto Protocol.

4.5.1. UNFCCC bodies

Since 2005, year of the entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol, the Conference of the Parties (CoP) is associated with the Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (MoP), the highest decision body of the Protocol. Countries having ratified the Convention but not the Protocol may attend the MoP but have no right of decision.

Both subsidiary bodies (SBSTA and SBI), and the Bureau of the Convention serve the CoP as the MoP. Concerning the Bureau, any member representing a non-Party to the Kyoto Protocol has to be replaced by a member representing a Kyoto Protocol Party to serve the MoP.

4.5.2. Constituted bodies under the Kyoto Protocol

Three bodies related to the implementation of the flexible mechanisms and to the control of compliance with Kyoto targets were constituted under the protocol:

- the CDM Executive Board: is responsible, under the authority and guidance of the CoP/MoP, for the accreditation of operational entities, other day-to-day management, preparation of decisions for the CoP/MoP and the supervision of the CDM mechanism;

- the JI Supervisory Committee (JISC): supervises the verification procedure related to the granting of ERUs and is under the authority and guidance of the CMP (Committee Members of the Parties);

- the Compliance Committee: it is the last of the Kyoto bodies established, it is in charge of the Compliance System, under the authority and guidance of the CMP. The meetings of the Compliance Committee are shared between the plenary sessions, the Enforcement Branch and the Facilitative Branch.

4.6. Kyoto and the transport sectors

In Annex A of the Protocol, where all sectors covered by the agreement are listed, energy is one of the five main concerned categories (energy, industrial processes, solvent and other product use, agriculture and waste).

This category comprises the fuel combustion sub-category (energy industries, manufacturing industries and construction, transport, other sectors, other) as well as the fugitive emissions from fuels. All GHG emissions related to the transport sectors are therefore covered by the Protocol, provided that:

- these GHGs are carbon dioxide (C02), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N20), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs) or sulphur hexafluoride (SF6);

- the emissions take place in a country that is part of the Kyoto Protocol;

- emission reductions are only mandatory if emissions occur in an Annex I country having ratified the Protocol;

- emissions are not due to international aviation and maritime transport (bunker fuels) seeing that these sectors are not included in the UNFCCC.

- the fuel/electricity consumption within the country

- or modelling approaches allocating emissions according to the distance travelled within the country and the associate fuel consumption.

5. The EU Emission Trading Scheme (EU-ETS)

5.1. Description

The European directive 2003/87/EC establishing a scheme for GHG emission allowance trading (EU-ETS) and its amending directive 2004/101/EC, the "linking directive" between the EU-ETS and the Kyoto Protocol, have established a CO2 emission market for big stationary emitters from the sub-mentioned sectors:

- power and heat generation industry ;

- combustion plants, oil refineries, coke ovens, iron and steel plants ;

- factories making cement, glass, lime, bricks, ceramics, pulp and paper.

- 2005-2007 : the test period ;

- 2008-2012 : the first Kyoto commitment period ;

- post-2012 : to be defined according to international negotiations at the UNFCCC level on the extension/modification of the Kyoto Protocol after 2012.

The mechanism is based on a "cap and trade" system with, during the first phase, at least 95% of emission allowances allocated free of charge to emitters according to their historical emissions ("grandfathering") and to their negotiation capacity with public authorities in charge of setting emission caps. In fact, the EU-ETS does not apply any global ceiling : it is a national-oriented system where each Member State decides for each phase, in a National Allocation Plan, how to share its Kyoto target between installations taking part in the EU-ETS and the rest of its GHG emitters covered by the Protocol.

The rest of the allowances are allocated to new entrants according to a benchmark.

Each year, emitters will have to comply with their own emission cap. Allowances can be sold on the market and bought by anyone. They can be "banked" by emitters in order to cover emissions for a coming year of a same period but it will be impossible to use allowances of one phase to cover emissions during another phase.

Member states are in charge of the establishment of a national emission registry in accordance with specific guidelines. Emission calculations and inventories are also harmonised within the EU and in accordance with IPCC guidelines for the UNFCCC by the methodology EMEP/CORINAIR.

5.2. EU-ETS and the transport sectors

Within the EU(25), the EU-ETS covers up to now +/- 11.500 stationary energy intensive installations, equivalent to ~2,2 billion t CO2 per annum (that is to say around 45% of European CO2 emissions or 30% of European GHG emissions (13).

Concerning transport modes, there are indirectly included in the EU-ETS as main refineries and power industry take part in the scheme but no direct GHG emissions from transport is concerned, from international aviation and maritime transport (bunker fuels) as well as from road / rail / domestic aviation / inland waterways transport.

However, the European Commission proposed on the 20th of December 2006 to include the aviation sector in the EU-ETS.

See "Synthesis over the inclusion of the aviation in the EU-ETS" for more details.